I knew they were coming, but I didn't know they were coming to us. Earlier in the morning, the news spread that the "rustling of leaves" will be heard once again tonight. After long years of absence, the "taong-labas" or "outside-people" are returning to this village.

I knew they were coming, but I didn't know they were coming to us. Earlier in the morning, the news spread that the "rustling of leaves" will be heard once again tonight. After long years of absence, the "taong-labas" or "outside-people" are returning to this village.

This morning, Mulawin and his wife engaged in a serious conversation with an old woman from a neighboring village. They were speaking in local Zambal dialect but I could get the drift of their conversation. The three of them had crumpled faces; at times they cursed the air.

"Tonight," Mulawin said, "the'barefoot men' might come to our village."

I didn't believe they were coming. I thought that the ongoing peace talks between the Communist rebels and the Philippine government were on the verge of completion and that both parties were about to sign an agreement. I thought the guerillas were preparing for that eventuality. I believed that there was no need for them to go to villages like this, since their presence creates more fear than sympathy.

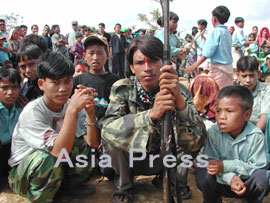

Comrade John and I shook hands. Other rebels emerged from nowhere, surrounding the hut. Mulawin woke up and came out. He couldn't believe his eyes. Comrade John introduced himself. Mulawin, looking hesitant, extended his right hand; his grip weak, touching only the tips of the rebel's fingers.

Some other rebels also introduce themselves. There are about ten of them and to my surprise, half are like Mulawin ? with dark, crinkly hair ? members of the same tribe. They are Aetas but they talk in Tagalog and the Pampanga dialect.

"So," I say to myself, "some Aetas too have joined the revolution."

By now, Mulawin's wife and two kids are awake. The glorious moon has leaned towards the west. Comrade John apologizes to Mulawin's wife for the disturbance. He is polite. Now, when visitors come you don't just let them gaze at the moon or stars. We entertained our guests. We boiled water and served them coffee. Once, twice, three times. The rebels gathered around the fire and laid their sleeping bags on the ground, their weapons beside them. Their lone female member couldn't find a space so I offered her my bed.

"Thank you," she said, "I'm Comrade Mary."

She has a long hair, a round face and a dark complexion. She moves with grace and is quite feminine. She wears fatigues but doesn't carry a rifle. She has a handgun that she wraps with cloth and places beside her pillow.

Comrade John beckons me to sit beside him.

"Comrade Rey," he began, "it must be clear to you that you are now under the jurisdiction of the people's revolutionary government, spearheaded by its advance forces, the Communist Party of the Philippines and the New People's Army."

How could I disagree?

"From now on," he went on, "we expect you to obey all revolutionary laws of this guerilla zone. You are now under our custody and you cannot leave this zone while the revolutionary forces are still here. This is for our security and likewise, yours. You are not being detained."

"From now on," he went on, "we expect you to obey all revolutionary laws of this guerilla zone. You are now under our custody and you cannot leave this zone while the revolutionary forces are still here. This is for our security and likewise, yours. You are not being detained."

Comrade John is a mild-mannered person. I didn't feel threatened or scared at all. In fact, I welcomed this encounter. It had been over a decade since I last spoke to them. I thought this could be an opportunity for a good conversation.

"We heard," Comrade John said, "that you are from Philvolcs (the Philippine Institute of Volcanology and Seismology). We gathered that you climbed Mount Pinatubo." All eyes were on me and I could sense Mulawin was beginning to get worried. His wife and kids went back to sleep.

"We have a comrade with us," Comrade John continued, patting the shoulder of a boyish rebel behind him, "whose idols include the scientist Kelvin Rodolfo."

"Hi," the young rebel raised his hand as he acknowledged me. "I'm Comrade Mark."

He is nineteen. He said he used to be a scholar at a science school in Manila. He left the bourgeois school, he said, to serve the masses.

"It was my dream," he said, "to be a scientist. In a way, I am a frustrated scientist. But I have transcended this selfish, personal ambition by becoming a revolutionary."

![<北朝鮮>[動画] 日韓で放映されたホームレス女性が死亡 <北朝鮮>[動画] 日韓で放映されたホームレス女性が死亡](https://www.asiapress.org/apn/wp-content/uploads/2010/12/201010070000000view.jpg)