Information on the true extent of the damage to the North Korean economy is carefully guarded by the regime. With 90 percent of trade lost, however, the impact must have been severe.

To find out the exact impact of the sanctions, ASIAPRESS worked with reporting partners living in various regions of North Korea to investigate. Through actual visits to the iron mines, fishing ports, regional trade offices, and Pyongyang markets, reporting partners were able to uncover the true effects of the sanctions on the lives of the North Korean citizens they met. To smuggle this information out of the country, reporting partners were asked to cross the border into China, through both illegal and legal means. Other reports were given through calls on smuggled Chinese mobile phones.

As the investigation progressed, it became clear that there is rising chaos in North Korea.

North Korean exports drop further than predicted

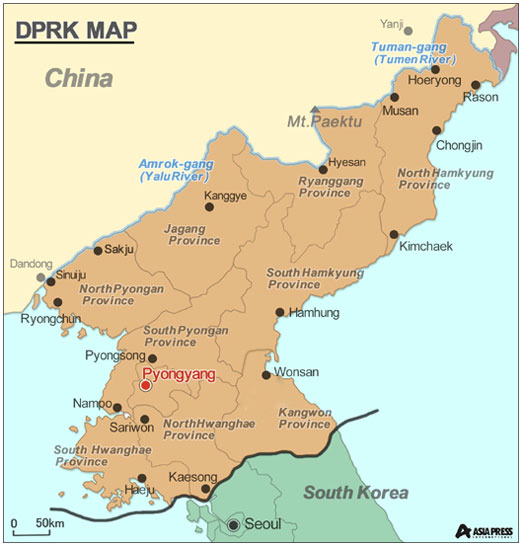

Let’s return to Musan County. Musan is on the border with China, facing the Tumen River, with a nearby iron mine providing work for much of its 100,000-strong population. The closeness of this mine to the border is convenient, as most of the iron produced is traded at the border. According to statistics from 2017, iron ore exports to China in 2014 amounted to $211.9 million and, for 2016, $74.41 million. Iron provided not just for Musan. As the second most important national export, the industry was regarded as a crown jewel among North Korean state-owned enterprises.

Our local partner set out to investigate the situation in Musan, reporting back that, “All operations at the mine were suspended apart from a small amount of mining at the domestic steel mills. The company can’t afford gas for its vehicles, so it has been renting them out to local businesses in an effort to recoup some losses. Food distribution to mine workers was suspended in March of last year. In July, workers received 4-5 kilograms of Chinese rice but following that, they didn’t receive anything at all until October. There are many hungry workers who have gone off to look for paying work elsewhere.”

‘Job desertion’ now a major crisis

All adult men in North Korea must work at jobs assigned to them by the government. In the 1990’s, a famine led to the dissolution of the food distribution system and, due to skyrocketing inflation, wages at most enterprises lost their value entirely. Despite this, North Korean men still had to report for work at their state-assigned jobs, mostly for the government to maintain control over their daily lives and political thoughts.

Workers have to sign in at their offices and, each morning, the police checks attendance registers. The Musan mine was one such employer where attendance was checked daily. The difference though was that due to the mine’s success, it was able to continue providing food and wages to an estimated 10,000 workers. After the sanctions, however, the mine could no longer support its workers and many began to desert their posts.

Last July, the reporting partner visited the house of an acquaintance who works in the mine. He said that a policeman had came earlier to the house to force him to go to work.

“The policeman decided not to drag the friend away once he saw how destitute his house was. Workers who were deserting were going into the mountains to collect herbs and vegetables to sell or eat. Workers who were not deserting their posts couldn’t work anyway because they were too weak from the hunger.”

Musan County is designated as a ‘hardship area’, with residents given corn and Chinese dried noodles. The region is on the cusp of a humanitarian crisis. Nevertheless, the authorities have refused to relax their control, prioritizing societal order over the lives of its citizens. Starting last fall, those who were caught repeatedly deserted their posts were sent off to labor camps.

In February, the local partner reported, “Workers at the mine have nothing to do even when they attend their posts. So they are being pressed into ‘construction brigades’ and sent to help with construction at a hydroelectric plant on the East Coast.”

The ‘construction brigades’ are units set up to lend labor to national construction projects, with members conscripted from state-owned enterprises and youth organizations.

Says the reporting partner on life in a construction brigade, “Food is provided on-site but the work is unpaid, with shifts lasting between 3-4 months. Everyone tries to forge medical certificates to avoid conscription, but it’s not easy.”

Next page>>>