◆ The sudden emergence of the market economy

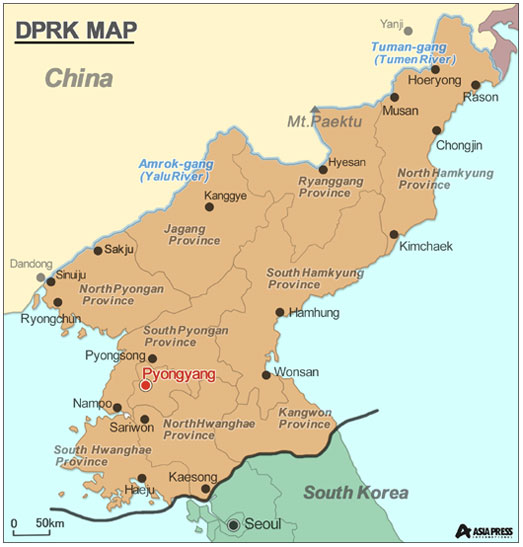

By the late 1990s, North Korea's socialist economy had largely collapsed, and markets, which had begun to spread organically, had taken over the distribution of all consumer goods, including food. The market economy continued to expand and spread despite several attempts by the regime to repressed it.

Although illegal, markets for housing, labor, and medical services emerged and became fully integrated into North Korean society. Private employment also spread, and small-scale businesses were tolerated. The majority of the general population did not receive food rations or salaries, but were able to buy food and other necessary goods in the markets with the cash they earned from their businesses and illegal labor.

Kim Jong-un's regime, which began in 2012, expanded trade with China while increasing the discretion of trading firms and businesses domestically, allowing for some degree of private economic activity. The period 2014-17 also saw an increase in the income of the common people.

◆ Major crackdowns began with the start of the COVID pandemic

At the onset of the pandemic, the Kim Jong-un regime prioritized epidemic prevention and sealed the country's borders to keep people and goods out. Imports of Chinese goods were halted, and the markets faced a brick wall.

The regime also severely restricted the movement of people and goods within the country, making it difficult to travel between counties and cities. At the same time, the regime intensified the "struggle against non-socialist and anti-socialist phenomena" that began before the pandemic, cracking down on private economic activities.

It became impossible to hire people to work in small-scale businesses, such as selling food products such as bread and rice cakes, sewing clothing, and transporting goods. Adult males were forced to report to their assigned workplaces, making it difficult for them to engage in commerce or menial labor. Those who left their jobs to pursue other livelihoods were punished as "job deserters" and the "unemployed.”

While all of this was happening, North Korea’s economy became paralyzed. In the fall of 2020, it became common to see processions of city dwellers going to the countryside to pick up leftovers from harvested crops. People begging for food at farm houses appeared everywhere.

In the summer of 2021, the number of people dying of malnutrition and disease began to increase, even in the vicinity of where our reporting partners live. Members of vulnerable groups such as families made up of mothers and children, the elderly, the sick, and the disabled began to collapse in exhaustion and hunger. Urban residents who had been deprived of the opportunity to earn cash income quickly became destitute.

◆ A shift to a state-run monopoly on food sales

Soon after the start of the pandemic, the Kim regime began to intervene in the sale of food in markets. It set price ceilings, forcing vendors to stick to them, and monitored stalls and kiosks. Next, it limited the amount of food sold in markets and cracked down on the flow of grain from rural areas to markets.

The regime passed measures to ensure that food would pass through “state-run grain shops,” a network of which the regime had been trying to build up since 2019. The shops monopolized the sale and distribution of staple foods, white rice and corn, and I thought it was a temporary measure to manage food during the coronavirus pandemic. However, it turned out that the real reason for this was something else.

◆ Ruling over people’s calories

Based on information from our reporting partners, since 2021, state-run grain shops have shifted from a sell-when-stock-is-available system to a twice-monthly sales system, with only 5 kilograms handed out to each person in a single household. As of December 2022, market prices were typically 6,000 won for white rice and 3,000 won for corn, whereas the state-run shops sold white rice for 4,400 won and corn for 2,400 won. (All prices are 1 kilogram; 1,000 North Korean won is about 155 South Korean won.)

Ordinary people welcomed the low prices at the shops, but the problem was that the shops didn’t provide enough stock to meet demand. Workers who showed up for work were given a few kilograms a month, but those who kept missing work were excluded from the ration system.

In January 2023, white rice and corn were finally banned from the markets. I believe that what the Kim Jong-un regime was aiming for was to take control of food distribution away from the market and shift to a “state-run monopoly on food.”

The goal of this policy is to reinstate the regime’s control over people’s calories. It's like saying, "I'll feed you, but you have to listen to me," and using food as a tool of control. How will the battle between the regime and the market end? ( To 4 >> )

- <Inside N. Korea> Government implements wage hike of more than 10 times (1) Wages increase for employees of state-run enterprises and government agencies

- <Investigation Inside N. Korea> How is the country’s fishing industry doing? (1) COVID and shrinking fishing grounds major problems…Kim regime’s restrictions on fishing lead some fishermen to financial collapse

- <Inside N. Korea> The Major Changes Surrounding the November 26 Elections(1) For the first time, multiple candidates on secret ballots for preliminary election…a small change in past elections

- <Inside N. Korea> Illegally printed study materials gain in popularity…How is this possible given N. Korea’s strict controls on publishing?

- <Inside N. Korea> A recent report on conditions at farms (1) The harvest is better than last year, but lack of materials remains a serious problem (4 recent photos)

![[Video Report] Why Do N.Korean Women Care About Looks? "I want to get attention from the guys.”](https://www.asiapress.org/rimjin-gang/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/333-150x150.jpg)