◆Authorities crack down on illegal loans by donju and cadres

Food-short households in rural areas have been given rice set aside by the state for emergencies, but they have to pay it back with interest in the fall, an ASIAPRESS reporting partner's investigation has found. The state is taking over usury, an illegal practice that has long been relied upon by urban donju (North Korea’s wealthy entrepreneurial class) and local officials, but why and for what purpose? (JEON Sung-jun / KANG Ji-won)

◆ Why is the state giving out food with high-interest rates?

In mid-April, some food-insecure households in rural areas received national emergency rice, according to a reporting partner in the northern part of the country. Food-insecure households are families who have run out of food at home and cash to buy food.

"Chinese rice was distributed (by the state), and for every kilo of rice, they deducted 1.3 kilograms from the distribution in the fall. The (interest) is lower than what private lenders charge, so people tried to get (the rice)."

The authorities have distributed food every spring to prevent farmers from not coming to work for lack of food. But this is the first time they've had to pay the food back with interest in the fall. Even then, the amount was not enough, and only food-insecure households received a week's worth of food.

Locals found it strange that while the state was cracking down on high-interest lending by individuals as non-socialist behavior, the state was now doing the same thing.

To understand why people think this way, let's take a closer look at the background of high-interest lending in rural areas.

◆ Why high-interest loans exist in rural areas

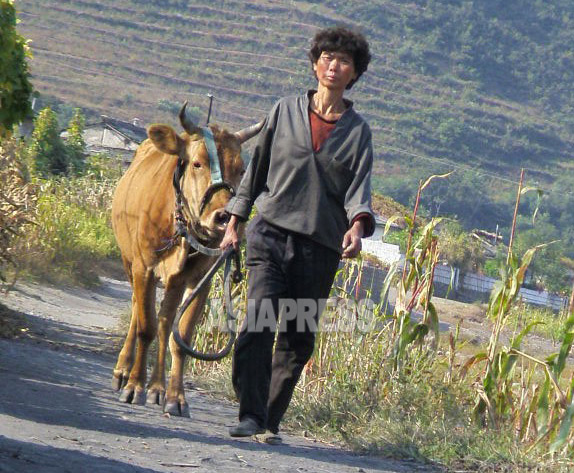

Spring is a difficult season for North Koreans, especially in rural areas, where winter food is scarce and grains such as barley and potatoes are not yet available, leading to the annual emergence of food-insecure households at this time of year, also known as the "Barley Hump."

The state has virtually ignored food-insecure households without taking effective measures against them. They borrow food from cadres with surplus food or from urban donju with interest, to be paid back in the fall. In rural areas, peer-to-peer lending has become a kind of bailout, given in lieu of direct government support.

But the problem was that the interest rates were too high. As the reporting partner mentioned earlier, if you borrowed one kilogram of food from a private lender in the spring, you would have to pay back two kilograms in the fall. That's 100% interest in less than half a year. The rural cadres and urban donju made huge profits, while those who borrowed food had their homes and lives destroyed.

People run out of rice before winter even arrives, and are forced to sell their homes because they have no way to repay the debt. The government has criticized this as a "modern-day landlord revival."

◆ Government crackdowns have not led to improvement

Since around 2019, Kim Jong Un's regime has been cracking down on usury in rural areas as part of its fight against non-socialism. Here are some typical examples sent in by our reporting partners in the northern region.

In December 2020, the authorities sent crackdown teams to rural areas in North Hamgyong Province to punish farmers, work unit leaders and other cadres involved in usury, and confiscated all food and cash obtained through usury.

In addition, the government announced to food borrowers that they would not have to repay the lenders if they reported usury, and encouraged them to do so anonymously, which reportedly resulted in many people getting out of debt.

The authorities' crackdown resulted in the confiscation of property and legal penalties for the moneylenders who had given out food on credit, as well as for urban individuals who had taken their wealth and invested it in rural areas. However, this later became a bigger problem as the authorities' crackdown left few people willing to lend food, leaving poor farmers to suffer the consequences.

Here is a report from a reporting partner in rural Ryanggang Province in April 2021.

"They treat those who fall prey to usury as exploiters like landlords and rich farmers, and urge us to fight against it as an act that eats away at a healthy socialist way of life."

The state's inability to solve their problems and cut off their only way to get by on credit has made it even harder for those in need, the reporting partner said.

◆ High-interest loans continue to be widespread in rural areas

This situation continued during the COVID period, and usury was reported to be widespread in rural areas. In early May, a reporting partner in Ryanggang Province said that while the authorities have stepped up crackdowns and punishments, the means and methods of usury are evolving.

"Even if the donju go to rural areas, they have to go through a distributor or a work unit leader who is in charge of distribution, but the distributor who was caught (in the crackdown) had stamped the contracts and kept them. During the house-to-house searches the contracts were found and the work unit leader was sent to a forced labor camp along with a member of the donju class."

But that's just the tip of the iceberg, according to the reporting partner.

"This time a sub-work unit leader was caught acting like a landlord, but I have heard that there are many donju who work quietly behind the scenes, collaborating with work unit leaders and other cadres. This means that people do what they can where they can.”

In addition, people who borrow food also keep their mouths shut in case times get really tough.

◆ Will the state formalize the practice of high-interest loans?

At this point, it's unclear how large or sustainable the initiative will be. As far as we can tell, the program is limited to rural areas in the northern area of the country. However, we cannot rule out the possibility that it will become formalized, as the benefits to the North Korean regime are significant.

First, state-led high-interest loans can prevent the damage caused by individual profiteering and prevent food-insecure households from starving. In fact, such a system has existed since the Three Kingdoms period as a kind of relief system, and the Hwangok system of the Joseon Dynasty also functioned as a social security system. Second, if the policy is institutionalized, it will secure tax revenue. Third, it would eliminate the non-socialist phenomena that the regime is so wary of.

But there are hurdles. One is the availability of enough food to sustain such a system. Another obstacle is the fear that the state's policy of collecting interest from the people will be seen as a retreat from socialist principles. This is because it may appear that the state is abandoning socialist principles in order to prevent individuals from becoming non-socialist.

Whether this change is a last-ditch effort by the authorities to get through the Barley Hump unscathed, or a first step toward institutional consolidation, it is significant that the Kim Jong Un regime has implemented such a measure at the national level as of spring 2024. Watch this space.

※ ASIAPRESS communicates with its reporting partners through Chinese cell phones smuggled into North Korea.

- <Inside N. Korea>Recruitment for the world's longest military service(1) This year 8 years for men, 5 years for women

- <Investigation>Why aren’t North Korea’s women having babies anymore? (1) The fertility rate is already severely low…It’s rare to see anyone carrying babies around

- <Inside N. Korea> Government confiscates private plots of farmland and forces people to return farming

- <Inside N. Korea>Chinese RMB exchange rate surges, up 42.8% since start of year...National police agency warns individuals and businesses against using foreign currencies

- <Inside N. Korea>Hungry elderly people flock to government office to demand rice, leading police to mobilize to put down unrest…Hyesan city