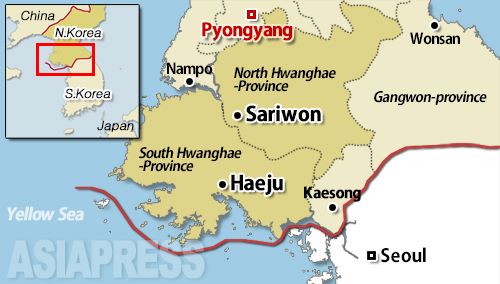

Kim Chung-yeol has experience farming on a large scale by leasing land from nearby collective farms to secure food rations for employees while working as a fleet captain at a fishery base belonging to a trading company near Haeju, Hwanghae Province. Hwanghae Province, with its Yeonbaek and Jaeryeong plains, is one of North Korea's major breadbaskets, particularly important for rice production.

The rural North Korea he experienced was far from the typical collective farm we might imagine. Instead, it was closer to a capitalist market economy. Through Kim's testimony, we can examine the current state of North Korea's rural economy.

◆ "I'll handle the state quota" - An offer that can't be refused

Q: We heard you farmed on leased farmland. How does this work?

Kim Chung-yeol: Typically, one work unit of a collective farm manages about 30 jeongbo (about 30 hectares) of land. But since the state can't supply fertilizer and farming materials on time, the work unit leader can't manage all that land. This causes problems meeting state quotas. So people with capital from nearby cities approach the work unit leader. They offer to provide funding for farming in exchange for land leases, proposing to take on part of the work unit's 'state quota.'

Q: How is the 'state quota' determined?

Kim: It's calculated by multiplying the land area managed by the work unit by the yield per pyeong(about 3.3㎡). The yield per pyeong is usually between 0.8 and 1.27 kilograms. This is how quotas are allocated to collective farms across North Korea.

Q: What happens after an agreement is reached?

Kim: After receiving the contract payment (farming supplies, money, or fuel), the work unit leader transfers farming rights to the contractor for that year. The contractor becomes responsible for securing fertilizer, seeds, machinery, and labor. They even have to handle workers' wages and meals. In return, they keep all harvest except for the state quota.

Q: When did individual farming on collective farms begin?

Kim: I'm not sure of the exact timing. But it's been happening for a long time. It became more common especially after COVID-19 erupted in 2020. Since the state couldn't properly supply fertilizer or seeds, farms couldn't farm properly. So gradually, giving land to individuals to farm on their own became normalized.

◆ Individuals achieving double what hundreds couldn't

Q: How do individuals farm the land they receive?

Kim: The actual farming is done by the farm workers belonging to the work unit. The contractor takes over management of the necessary workers for the year from the work unit leader. In my case, I chose one farming technician and three farm workers. I paid them 3,000 won (North Korean currency) per day, equivalent to about 1.5 kilograms of corn. I also provided lunch. While the daily wage might seem low, it's much better than working for the farm. Plus, they can avoid state assignments and various mobilizations, so it's much better than wasting time on unpaid state work.

For times when we need extra hands, we hire other farm workers on a temporary basis. We pay them daily wages and provide a filling lunch of noodles. For tasks like rice transplanting, we might hire 80 to 100 people and finish it all in one day. While people might work half-heartedly on state projects, it's different here because they receive immediate payment.

Q: What about the harvest rate, and how is the harvest distributed?

Kim: The contractor takes everything after fulfilling the state quota. In my case, I had about 10 tons of rice as net profit. But you don't keep all of it - there are many inspections. There are lots of inspectors. You have to generously cut off portions as bribes for them to avoid trouble. Some goes to the workers' rations, and the rest is mine.

◆ Good for everyone but the state - why?

Q: What benefits do farm officials receive?

Kim: Farm officials just need to meet the quotas from above. Whether it's military rice quotas or state quotas, they're overwhelmed, but since I produce and deliver it myself, the officials can avoid the hassle of managing land and controlling workers. They don't have to worry about missing quotas due to lack of farming funds or materials. Plus, there's a lot of bribery involved in securing contracts. So it's perfect for farm officials. What hundreds of farm workers couldn't achieve, an individual can double.

Q: In your opinion, how widespread is this phenomenon across North Korea?

Kim: I'm not sure about nationwide, but Hwanghae Province has many plains, so it's quite popular there. In my case, it's actually modest - there are wealthy individuals who tell the county party secretary or management committee chairman they'll handle hundreds of tons of work unit quotas if they're given all the farm workers and left alone. I was surprised to find that in Byoksong (South Hwanghae Province), there were cases where individuals operated entire villages this way.

Q: How are the authorities responding to this?

Kim: Around 2022, they heavily cracked down on the “crime of labor exploitation,” saying they would punish individuals hiring farm workers for farming. It's ironic that it's fine for the state to exploit farmers' labor without compensation, but individuals can't pay wages to others for work. It's contradictory.

However, there are many ways to avoid crackdowns. As long as you keep the officials quiet, you can operate without much problem.

Kim's testimony vividly shows the dynamics of spontaneous marketization occurring in North Korea's rural areas. Despite various crackdowns and controls by North Korean authorities, residents seem to be creating their own new economic order. It bears watching whether these movements can become a force for fundamental change in North Korean society, beyond mere survival efforts to avoid hunger. (End)

- <Lighting Up N. Korea's Four Dark Years> (9) The Capitalist Ghost Under the Socialist Roof (1): From Private Ship Owners to 'Unions' Negotiating with the Central Party... Ship Owners Pushing Boundaries

- <Lighting Up N. Korea's Four Dark Years> (8) Pandemic-Induced Financial Crisis and the Regime's Response: 'Tax-Free' North Korea Imposes New Levies, Including 'Fireplace Tax'

- <Lighting Up N. Korea's Four Dark Years> (7) North Korea’s Pandemic Power Play: State Seizes Market Control as “Donju” Crumble

- <Lighting Up N. Korea's Four Dark Years> (6) Humanitarian Crisis is a Man-Made Disaster: Intensifying Chaos and Disorder... North Korean Version of 'War on Crime' as Told by COVID Survivors

- <Lighting Up N. Korea's Four Dark Years> (5) What Happened During COVID... "Drink Willow Branch Brew" - Misguided Quarantine Policies Only Led to Residents' Deaths

- <Lighting Up N. Korea's Dark Four Years> (4) “The People Are at the End of Their Tether”: A Country that Wants to Control Markets and Rule by Calories

- <Lighting Up N. Korea's Dark Four Years> (3) The Second Link in the Tragedy – Ruthless Quarantine Policy, "The State is Scarier than the Virus"

- <Lighting Up N. Korea's Four Dark Years> (2) The First Link in a Tragic Chain - Border Closure... "Corona Was a Nightmare, It Was Difficult to Buy Even a Single Needle"

- <Lighting Up N. Korea's Four Dark Years> (1) Almost the Only Escape Route -The New Generation ‘Donju’ Who Crossed the Sea Tell About COVID-19, Chaos, and Social Change