<Lighting Up N. Korea's Four Dark Years> (1) Almost the Only Escape Route -The New Generation ‘Donju’ Who Crossed the Sea Tell About COVID-19, Chaos, and Social Change

The pandemic was not only a difficult time for North Korean citizens, but also a serious ordeal for the North Korean regime. The financial shock inflicted on the regime by the pandemic is confirmed by various statistics and appears to have been a significant pressure to maintain the system. To overcome this, the North Korean regime began to take control of the market economy. This article examines this process. (JEON Sung-jun)

◆ The First Way Out of the Financial Crisis – Market Control

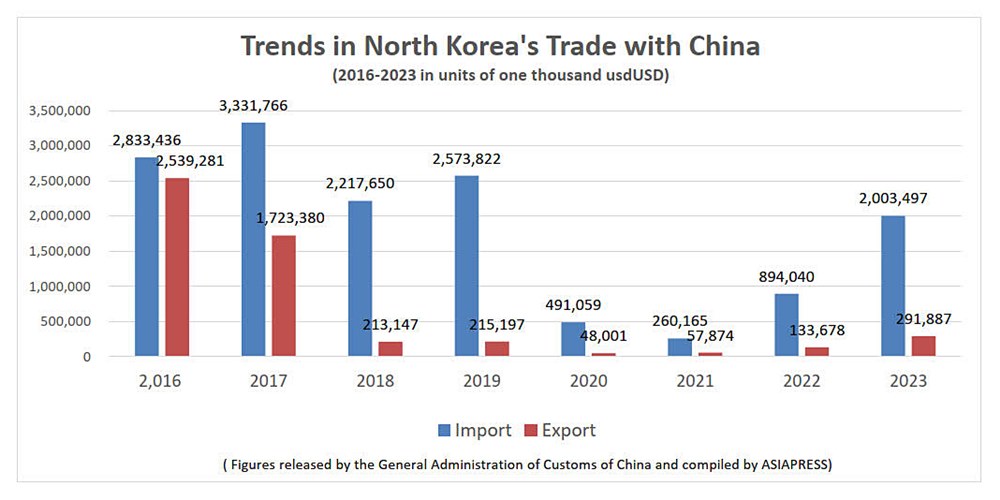

The North Korean regime's decision to close its borders and isolate itself backfired, creating a self-defeating situation. As major sources of government revenue—such as trade with China, overseas labor, and tourism—were cut off, foreign exchange earnings plummeted. Backed into a corner, North Korean authorities had to find a way out, and their first move was to seize control of the market economy.

Since the mid-1990s, a spontaneously developed market economy had grown to rival North Korea's official economy in both size and impact on the population. The scale of this market economy is best exemplified by the "jangmadang" (marketplaces), often referred to as the cornerstone of North Korea's unofficial economy. According to the "2022 Status of North Korea's Official Markets" report published by the Korea Institute for National Unification, there were 414 such markets in North Korea as of November 2022. The fees collected from these markets are estimated to reach up to $306.4 million annually—far surpassing North Korea's exports to China in 2021, which stood at just $57.9 million.

Kim Chung-yeol observes that the market, rather than the state, became the primary provider for residents, leading to the emergence of a new wealthy class.

"The market allowed many people to become relatively well-off," Kim explains. "As individuals became financiers and ship owners and started making money, they could afford better food and make new investments. This gradually improved people's overall standard of living. It wasn't due to state policies, but because we, the younger generation, worked hard and engaged in business, motivated by the hardships our parents and grandparents endured."

For the regime, North Korea's market economy was a goose that laid golden eggs. However, faced with a financial crisis, the authorities grew dissatisfied with just these "golden eggs." The Kim Jong-un regime launched an ambitious plan to monopolize the profits generated by the market economy, aiming to overcome the crisis through strict market control. Yet, their actions seem to be leading toward a situation akin to killing the goose that laid the golden eggs.

◆ The Fall of the 'Donju'

The term 'donju' refers to the entrepreneurial wealthy class that emerged in North Korea following the 'Arduous March' famine of the 1990s. These individuals amassed wealth as the market economy grew, typically including traders (and smugglers), transportation business owners, ship owners, wholesalers, and money changers.

The donju built their fortunes primarily through profit-generating assets such as connections with Chinese trading partners, vehicles, fishing boats, and real estate. In doing so, they inadvertently promoted the marketization of North Korea's economy.

However, the COVID-19 pandemic turned North Korea into a graveyard for the donju. According to Kim Myeong-ok, their downfall began in the early stages of the pandemic.

"During the COVID period, all the donju collapsed," she states.

Kim points to the authorities' tight control over foreign currency circulation as the first blow to the donju's empire.

"When the state initially banned the use of dollars, the exchange rate plummeted from 80 (800,000 North Korean won to $100) to 40," Kim explains. "Fearing their money would become worthless, people rushed to exchange everything at these low rates. Later, though, the state raised the rates again."

The authorities' complete ban on foreign currency use and subsequent crackdowns led to wild fluctuations in dollar and yuan exchange rates, a pattern observed multiple times throughout the pandemic.

Kim Myeong-ok notes that the closure of export channels dealt another severe blow to the donju.

"Some donju had invested tens of thousands of dollars in buying scallop seeds from China to start farms," she recounts. "But when the border closed, they couldn't export. Their investment became worthless, and they all went bankrupt."

Kang Gyu-rin, a former fishing boat operator, describes how ship owners also fell victim to pandemic policies.

"In coastal areas, there was an order to destroy all wooden boats," Kang says. "But these boats represented huge investments—about $10,000 each. Unable to destroy them, the owners left them on land for three years. Wooden boats deteriorate quickly on land, becoming unusable. All the ship owners went bankrupt. They used to be wealthy, but all that money essentially evaporated."

Moreover, the strict border closure wiped out the smugglers operating in border areas. As smuggling operations collapsed, it triggered a domino effect, bankrupting donju involved in transportation and wholesale businesses along the smuggled goods supply chain.

◆ The State is 'Doing Business' Under the 'Socialist Flag'

The market panic triggered by the pandemic presented an unexpected opportunity for North Korean authorities. They effectively tapped into the financial resources left behind by the fallen donju. Ironically, the Kim Jong-un regime, which publicly advocates for anti-market measures, is now profiting from the very market it criticizes.

The authorities' current approach seems to straddle a line between anti-market and pro-market policies. It's anti-market in that it strips individuals of their right to participate freely in the market. Yet, it's pro-market in the sense that the state has seized control of the market economy's mechanisms, aiming to use its profits as a source of financial security.

Kim Myeong-ok points out this contradiction:

"The state loudly proclaims socialism, but behind the scenes, it's practicing capitalism. They're essentially saying they'll take everything from individuals and run businesses as the state."

What's particularly noteworthy is the method employed. The state is indirectly restructuring the economy by granting business rights to select individuals and then imposing taxes on them. This approach appears strategic, allowing the state to maintain control over the market while simultaneously reaping its profits.

Let's examine these specific methods in more detail.

◆ The Reality of 'State-owned' Enterprises

As the number of donju—who had been adept at meeting public demand and ensuring smooth supply—decreased, "state shops" began to proliferate, ostensibly filling the market void. These included 'state-owned stores', 'state-owned pharmacies', and 'grain sales stores'.

Grain warehouses and pharmacies are prime examples of this trend. During the pandemic, North Korea blocked all individual sales of food and medicine, restricting transactions to state monopoly stores only.

While some interpret these measures as North Korea's return to a planned economy, defector interviews paint a different picture. They reveal that these "state stores" are actually run by individuals, operating in a thoroughly capitalistic manner.

Kim Chung-yeol offers insight into the "grain sales stores" that emerged around 2022:

"They're called state-owned, but individuals run everything. The operator enters the business with grain sales rights granted by the state. Essentially, it's a system where the state strips rights from ordinary people and hands them to select individuals, making it easier for the state to intervene and extract money."

Kang Gyu-rin's testimony suggests that state-run pharmacies operate similarly:

"Pharmacies follow the same model as grain stores. Ultimately, it's a setup where individuals invest and operate within government buildings. It has to work this way because the state can't afford to finance everything itself. So, a wealthy individual steps in to run the business, but under the state's name. You get state approval, but in exchange, they take a larger cut. For instance, if today's income is 100,000 won, they immediately claim about 40%."

This system allows the state to maintain the appearance of control while leveraging private capital and entrepreneurship, all while securing a significant portion of the profits.

◆ Even 'Money-making Trains' Using State Railways Appear

Kim Myeong-ok reveals that the state has even ventured into the railway business:

"Now we have what you might call 'profit-making trains.' These are diesel-powered locomotives that are quite noisy and belch black smoke. They're running under the banner of state business and are slightly cheaper than the private 'money-making cars'."

These 'money-making cars' have been a hallmark of North Korea's market economy since the "Arduous March" famine, with private vehicles transporting both people and goods across the country.

While the exact operational details remain unclear, the emergence of state-run "profit-making trains" in the railway sector—long emphasized as the backbone of the people's economy—is particularly significant.

Another example of this trend is the Cooperative Currency Exchange. This state-owned institution has replaced private money changers who previously handled both currency exchange and informal lending. Now, all foreign currency exchanges must go through this official channel.

ASIAPRESShas documented various other instances of this shift, such as the granting of fishing rights to certain companies in exchange for a share of their catch, and the introduction of card payments for market fees. These moves appear to be part of a broader strategy by the regime to centralize profits that were previously dispersed among individuals, mid-level cadres, and local governments.

In our next installment, we'll explore how the authorities continue to exploit the population as another means of addressing their financial crisis. (To 8 >>)

<Lighting Up N. Korea's Four Dark Years> (6) Humanitarian Crisis is a Man-Made Disaster: Intensifying Chaos and Disorder... North Korean Version of 'War on Crime' as Told by COVID Survivors

- <Lighting Up N. Korea's Four Dark Years> (10) The Capitalist Ghost Under the Socialist Roof (2) "Leave the Quota to Me" - Are Wealthy Individuals the Driving Force of Rural Economy?

- <Lighting Up N. Korea's Four Dark Years> (9) The Capitalist Ghost Under the Socialist Roof (1): From Private Ship Owners to 'Unions' Negotiating with the Central Party... Ship Owners Pushing Boundaries

- <Lighting Up N. Korea's Four Dark Years> (8) Pandemic-Induced Financial Crisis and the Regime's Response: 'Tax-Free' North Korea Imposes New Levies, Including 'Fireplace Tax'

- <Lighting Up N. Korea's Four Dark Years> (6) Humanitarian Crisis is a Man-Made Disaster: Intensifying Chaos and Disorder... North Korean Version of 'War on Crime' as Told by COVID Survivors

- <Lighting Up N. Korea's Four Dark Years> (5) What Happened During COVID... "Drink Willow Branch Brew" - Misguided Quarantine Policies Only Led to Residents' Deaths

- <Lighting Up N. Korea's Dark Four Years> (4) “The People Are at the End of Their Tether”: A Country that Wants to Control Markets and Rule by Calories

- <Lighting Up N. Korea's Dark Four Years> (3) The Second Link in the Tragedy – Ruthless Quarantine Policy, "The State is Scarier than the Virus"

- <Lighting Up N. Korea's Four Dark Years> (2) The First Link in a Tragic Chain - Border Closure... "Corona Was a Nightmare, It Was Difficult to Buy Even a Single Needle"

- <Lighting Up N. Korea's Four Dark Years> (1) Almost the Only Escape Route -The New Generation ‘Donju’ Who Crossed the Sea Tell About COVID-19, Chaos, and Social Change

![<Inside N. Korea> The Deteriorating Plight of the People (2) Kim Regime Prioritizes Order Over Welfare [ISHIMARU Jiro]](https://www.asiapress.org/rimjin-gang/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/202107-dandong-03_logo-150x150.jpeg)